Frederick Augustus Boden

Frederick Augustus Boden

John Wallace Bull

John Wallace Bull

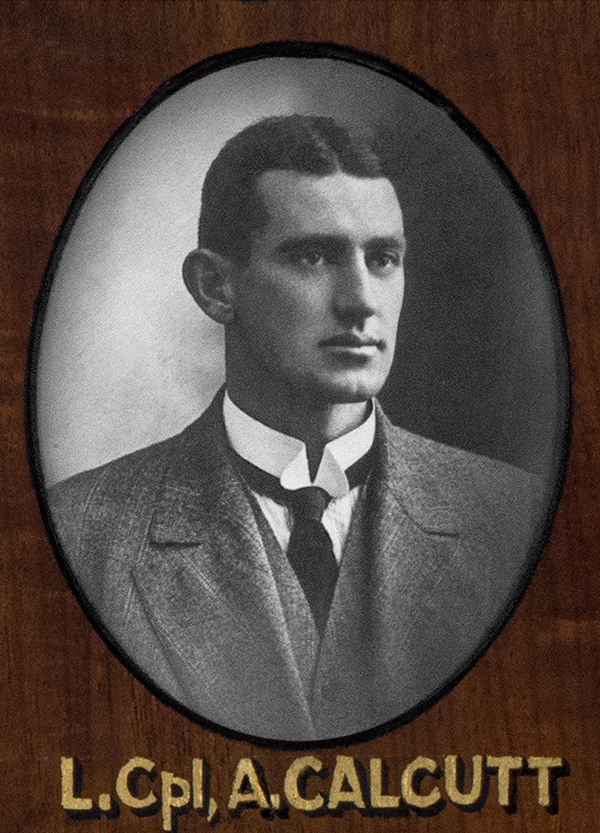

Gerald Calcutt

Gerald Calcutt

Norman Leslie Critten

Norman Leslie Critten

David Leo Dorgan

David Leo Dorgan

Although a hundred years or more have passed since the deaths of the servicemen depicted in the photographs on the Williamstown Town Hall Honour Board, their portraits still have the power to move us. We see the impossibly young, the roguish, the clean cut, the curly haired sons, the dashing airmen with their collars up, the sailors – the moustached sergeant, the older fellows – serious, some nonchalant, the smiling, the fearful ones, and those who stare straight out – eyes clear and forward – sure of themselves, almost defiant, reaching through time.

The Melbourne commercial photographer, Algernon Darge had a concession to take photos of soldiers at Broadmeadows and Seymour Camps. He photographed 19,000 soldiers before they embarked for overseas service. It’s mainly thanks to Darge and those images sent by the men to their families that Cr Henderson was able to collect photos for the board at Williamstown Town Hall. Darge’s immense catalogue of glass negatives and notes were purchased by the Australian War Memorial in the late 1930s.

Many soldiers carried small cameras and took snaps during the fighting in Gallipoli and Egypt. The Kodak Vest Pocket camera was a popular model as it was small and could be folded flat when not in use. Kodak quickly saw a promotional opportunity and advertised it as the ‘Soldier’s Kodak’. ‘Every soldier naturally wants to keep a lasting record of the brave part he and his own company is playing in the Great War – and he can do it well and easily with the little Vest Pocket Kodak’.

At the same time newspapers offered money for pictures of the action and prize money for the best photographs – it was possible to win £1000 if your photograph was chosen to be enlarged and published.

As the carnage and death toll of the war rose and the military sought to manage public perception, letters were censored and personal cameras banned. A soldier caught carrying a camera could be immediately arrested and court martialled. Even Australia’s war correspondent Charles Bean was banned from carrying a camera.

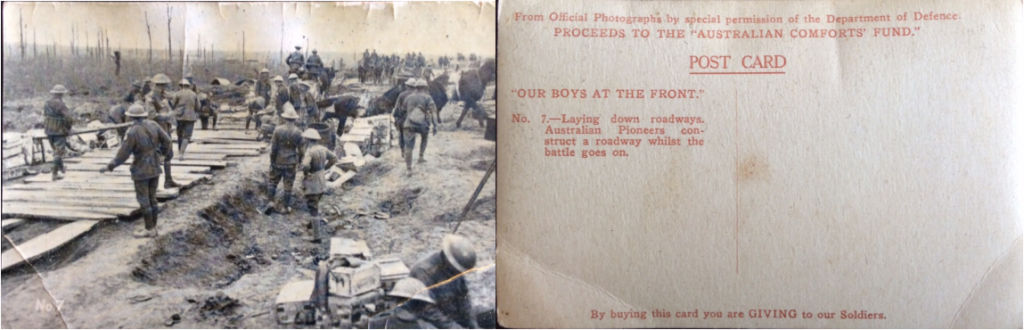

Prior to the outbreak of WW1 postcards, a common way for friends and relatives to communicate, were popular to collect and save. The military took advantage of this popularity during the horrors of the war. Official photographic postcards were produced by special permission of the Department of Defence not only to raise money but also for propaganda and to encourage enlistment.

Official postcard from the George McInnes biography courtesy Mairi Neil

Hilary Roberts writing on the role of photography in WW1

“British colonial forces, such as the Australian, New Zealand and Canadian expeditionary forces, relied heavily on British support for official photography on the Western Front. Four out of the seven colonial official photographers who covered the Western Front during this period were, in fact, British. The remit of the colonial photographers, like that of the French and British official photographers, was to take photographs for information, propaganda and the historical record. However their work reflects clear differences in the interpretation of this remit. The British photographers, of necessity, prioritized news and propaganda over that of record. The Australians, directed by Charles Bean in his capacity as official correspondent and historian, took great pains to create a detailed and truthful record for future generations. Hubert Wilkins to whom Bean allocated “record work” in 1917, recorded graphic scenes that were unlikely ever to be used for wartime news or propaganda.”

References:

Sydney Morning Herald, 4 May, 1915, p.6 in Maynard, The Unseen Anzac, p. 34, 35

Australian War Memorial, Up front: faces of Australia at war: catalogue essay

To read more on the role of photography during World War 1:

Hilary Roberts, International Encyclopedia of the First World War

Citation

Roberts, Hilary: Photography, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15463/ie1418.10142.

Header images courtesy Australian War Memorial